Should Sub Saharan Africa make Its Own Pharmaceutical Production?

Introduction

With imports comprising as much as 70-90 percent of drugs consumed in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, many governments are considering whether it’s time to promote more local production. Drug imports, including both over-the-counter and prescription drugs, considerably exceed those into China and India. In China, comparable populations import around 5 percent, while in India, it is around 20 percent. And it does put a strain on government and household budgets and already limited foreign exchanges.

Systematic Analysis

a) Promoting Local Drug Production

To better understand the realities of promoting local drug production, we undertook a systematic analysis of the current state of the market. The analysis focused on simple, small molecules, such as generic drugs, since the economics and technical challenges would vary for more complex products, such as combination drugs, injectables, and vaccines. We evaluated the costs and benefits of increasing production not only in economic terms but also in their impact on the wider economy and on public health systems. We then compared that to local measures of feasibility, including government will, demand, investment attractiveness, and implementation capacity, especially with respect to quality.

Exhibit 1

The analysis reveals varying opportunities across different countries. Some may find establishing a manufacturing hub economically unfeasible due to factors like a small market, global excess of manufacturing capability for certain drugs, unreliable infrastructure, and limited talent base. However, for a few countries, such a hub could be viable if they overcome these obstacles. A local industry could modestly reduce drug costs and enhance access to drugs, particularly for non-affluent consumers. It might also benefit public health as donor programs face budget constraints. Nevertheless, the impact on jobs and GDP would likely remain minimal compared to the overall size of these economies.

Exhibit 2

In sub-Saharan Africa, only Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa have a relatively sizable industry, with dozens of companies that produce for their local markets and, in some cases, for export to neighbouring countries. Local producers also play in a limited range of the value chain. Almost all of them are drug-product manufacturers—that is, they purchase active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from other manufacturers and formulate them into finished pills, syrups, creams, capsules, and other finished drugs. Up to a hundred manufacturers in sub-Saharan Africa are limited to packaging: purchasing pills and other finished drugs in bulk and repackaging them into consumer-facing packs. Only three—two in South Africa, and one in Ghana—are producing APIs, and none have significant R&D activity.

Pharmaceutical production in sub-Saharan Africa lags behind comparable regions.

Some African countries have a handful of local companies that produce for the domestic market. Most do not—and are currently uncompetitive for local drug production (Exhibit 2). The continent overall has roughly 375 drug makers, most in North Africa, to serve a population of around 1.3 billion people. Just nine out of 46 countries in sub-Saharan Africa largely cluster those, and they are mostly small, with operations that do not meet international standards. By comparison, China and India, each with roughly 1.4 billion in population, have as many as 5,000-10,500 drug manufacturers, respectively. And the sub-Saharan market’s value is still relatively small, at roughly $14 billion compared with roughly $120 billion overall in China and $19 billion in India.

What’s the value of increased local drug production?

Developing a local drug industry in sub-Saharan Africa would take decades of sustained and careful effort. Examining the value of such an undertaking involves more than the economics of individual-company-level business. Pharmaceutical products have wide-ranging effects, leading governments and citizens to consider their impact in broader economic terms like economic growth and job creation. Additionally, they are evaluated in terms of public health, including access to medicines and preparedness for disease outbreaks. To examine which dimensions really matter, we disaggregated the notion of impact into affordability, health impact, and economic impact.

b) More affordable drugs

Public-health officials and potential investors frequently argue variously that locally manufactured drugs would be cheaper once all the costs are factored in, while others take it for granted that it’s cheaper to produce drugs in India than in Africa. The analysis suggests some truth to both arguments: drugs are currently cheaper when imported, but with comparable facilities, some drugs in the future could be cost-competitive or even cheaper than imports from India. This is more likely true of basic oral solids than more advanced and larger-molecule drugs.

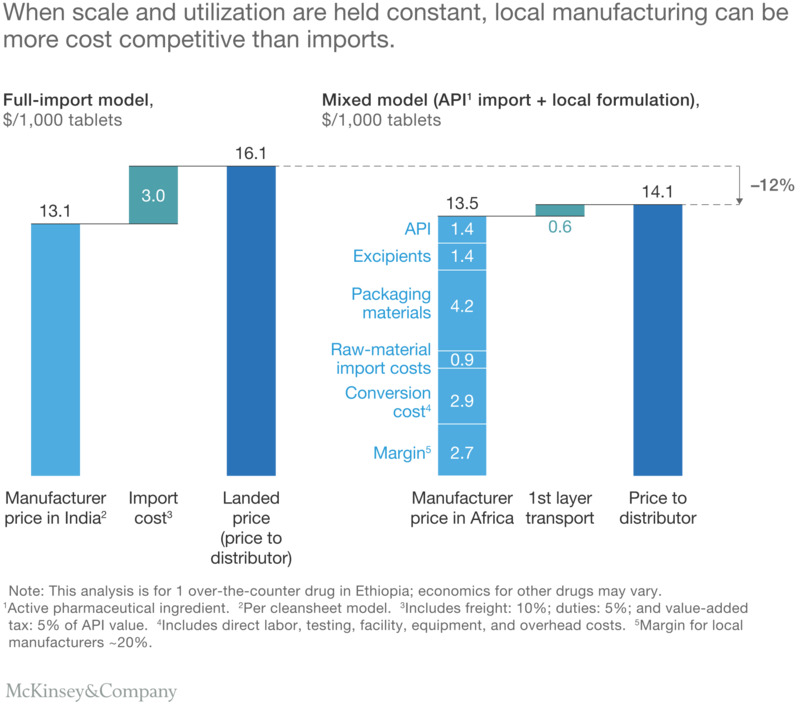

Comparative Analysis of Drug Manufacturing Costs: A Case Study of Ethiopia’s OTC Drug Industry

In our modelling of comparable plants producing a common over-the-counter drug, we observed that importing the drug to Ethiopia includes a manufacturer’s price in India plus a more-than-20-percent markup due to freight, duties, and value-added tax. However, if the same drug were manufactured in Ethiopia, the import costs for raw materials would be lower due to their relatively low value. Although the locally manufactured product’s price would be higher than in India due to lower manufacturing efficiency and producer margin, the lower transport cost to reach the distributor makes it more affordable at the point of entry into the local supply chain. In fact, for various products, including tablets, capsules, and creams, the costs of most drugs produced in Ethiopia and Nigeria tend to be about 5 to 15 percent lower than the landed price of imports from India.

Improved public health

Increased pharmaceutical manufacturing can affect a population’s health in various ways, such as its access to, awareness of, and availability of needed medicines. It can also impact the systems that regulate quality and safety. Each country’s configuration of the health system and health market heavily influences these effects, and they will vary country by country. Yet our analysis for Ethiopia and Nigeria highlighted some effects that may be applicable for other countries as well.

Global drug originators often lack incentives to register and promote all their products in small African country markets, resulting in limited access to medicines, including outdated drugs. Many African countries still use older drugs not recommended by the WHO’s essential drug list. Local manufacturers, on the other hand, have the motivation and resources to introduce newer generation generics in smaller African markets. In Ethiopia, a local player’s production of a newer-generation antibiotic led to its inclusion on the list of products available to public health facilities. In Nigeria, regulations allow local drug manufacturers to be drug importers, and many leading local manufacturers represent global drug originators, encouraging investment in local drug registration and the introduction of lucrative new products. While Nigeria stands out as a potentially lucrative market, increased local drug manufacturing’s impact in most other countries is expected to resemble the economics in Ethiopia more closely than in Nigeria.

Another arena in which we expect increased local drug production to have positive effects is in the regulation and quality assurance of drugs in local African markets. In Ethiopia, for example, the government’s desire to spur local drug manufacturing has come hand in hand with a commitment to strengthen its national drug regulator, the Food, Medicine, and Health Care Administration and Control Authority. The government has also committed to reducing delays in product registration, ferreting out counterfeit drugs, and pushing manufacturers to meet standards required for exports. Overall, Ethiopia is investing ahead of the curve in regulatory capacity. Although its pharma market is only valued at approximately $600 million, its regulator has a budget of $6.6 million, which is a higher ratio than observed in Brazil, Russia, and Turkey.

Improved economy

Proponents of local drug manufacturing in sub-Saharan Africa often express their argument in economic terms: economic diversification, GDP growth, the impact on the balance of trade, and job creation. However, our analysis suggests that pharmaceuticals would remain a relatively small sector of the overall economy, even assuming significant growth. The effect on annual GDP growth would likely be negligible—on the order of $190 million per year by 2027 for Ethiopia and $230 million per year for Nigeria, over a period when we project annual growth for the two countries could be on the order of $14 billion and $27 billion, respectively.

The largest effect would be on the balance of trade. If Ethiopia and Nigeria were to increase their local share of production from roughly 15 to 20 percent to around 40 to 45 percent, both countries could expect to see their trade balances improve by $150 million to $200 million annually. In Ethiopia, trade imbalances have been a critical issue for several years as the country has dealt with a severe shortage of foreign exchange. A swing of a couple of hundred million dollars in a decade’s time would certainly be welcome. But it would be hard to feel, since it amounts to less than 5 percent of Ethiopia’s projected foreign currency needs—not including the additional capital investments needed to build industrial parks and upgrade national regulators.

An increase in local production would not create many jobs. Modern pharmaceutical plants employ only a few hundred workers. New entrants tend to be even leaner: the two new Chinese entrants into the Ethiopian market, for example, are building more automated production facilities and hence employ only around 200 workers on average. Altogether, the total job creation affected by increased local pharmaceutical production is likely to be on the order of a few thousand jobs at best—even including any impact it has on jobs upstream and downstream, in its suppliers and distributors.

Is it feasible?

The feasibility of building an industry in any country is influenced by both private- and public-sector factors. On the private side, the inherent market dynamics, and the attractiveness of available investments, will determine whether there is a strong business case for putting money into the pharmaceutical sector. These include, for example, whether there’s enough unmet demand to make a sizeable plant competitive and the practicalities of exporting excess production. On the public side, governments have several potential levers to encourage local production. These include local production incentives in national tenders, subsidies and tax breaks, investment in special economic zones, and talent- and skill-building programs. The availability of these levers varies across countries, and individual governments’ attitudes toward the pharmaceutical industry influence their willingness to employ these levers.

Overall, our analysis convinced us that increased local drug production is feasible in about a half dozen sub-Saharan African countries at current and projected demand levels. While only South Africa is currently as attractive to private-sector pharmaceutical investors as Brazil and India, other countries are rapidly improving their investment climate. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses relative to Brazil, China, and India. Some are stronger in areas like logistics, business climate, and tax policies. Others might do well in some areas, such as tax policy, logistics, and technology, but show weaknesses in government and business climate. Still others could quickly become attractive to international investors with continued improvement.

Creating a sustainable pharma sector in sub-Saharan Africa.

In those countries where increased local production of pharmaceuticals would be both feasible and have a positive impact, the question is how to do it. Through our research, we have distilled five lessons that could help them do so in a way that contributes most to the health of their people and the well-being of their economies. These include a focus on quality, production capacity (or scale), regional hubs, drug-product formulation, and value-chain effects.

Focus on quality

Regulatory standards and enforcement across sub-Saharan Africa typically lag behind global standards. There are only six companies operating in the region that have achieved WHO prequalification.3 The fight against counterfeit, expired, and substandard drugs is improving, but it is still common in some countries in the region.

As sub-Saharan Africa develops its local pharmaceutical industry, it is imperative that countries continuously upgrade their quality standards and enforcement. Beyond saving lives, a stronger regulatory system would allow for a fair and competitive playing field, eliminating low-priced, substandard products from the market. To do so, country leaders may need to commit to ongoing funding for their regulatory agencies in accordance with established global benchmarks or perhaps consider continent-wide efforts such as those in Europe. This would allow regulators to address some of the existing gaps in training, capabilities, and manpower in regulatory oversight and quality control. Another priority should be cultivating and sustaining a healthy pipeline of regulatory talent, since turnover is brisk for many agencies as trained staff quickly leave for private-sector jobs.

Build plants with sufficient production capacity.

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa might enjoy theoretical production-cost advantages, but their lower production capacity and utilization relative to India could outweigh those benefits. Most production in the region today occurs in small plants with low capacity—plants need to be big enough and have sufficient capacity to leverage the benefits of scale economics. Additionally, unreliable infrastructure, frequent power interruptions, and high logistics costs affect utilization.

At what point would manufacturing plants there become competitive with imports? According to our analysis, production volume—that is, the plant’s capacity times utilization—affects economics and affordability disproportionately more than other commonly cited concerns, such as labor productivity and electricity costs. The cutoff for output depends on product type, but for a tablet-based product it would be around 500 million tablets (Exhibit 4). Smaller plants are unlikely to be competitive with imports, even running at full utilization, and plants operating below the cutoff today may not be sustainable over the long term.

Thus, as companies in sub-Saharan Africa upgrade old plants and build new ones, they should ensure that they meet a certain threshold of production while also ensuring that there is sufficient market demand to maintain health utilization. Companies should estimate the necessary break point for their specific mix of products and location, and plan their investments accordingly. Country governments might also reconsider incentives to companies that meet competitive levels of production.

Create regional hubs that include smaller countries

Sub-Saharan African countries can collaborate to promote a few globally competitive industry clusters due to minimum production requirements and limited feasible locations for pharmaceutical manufacturing. These clusters are more likely to produce affordable, high-quality drugs compared to scattered subscale investment attempts across the continent. Regulatory harmonization can lead to faster lead times and more responsive supply chains, benefiting smaller countries with local suppliers instead of overseas ones.

There is already a broader movement to create freer trade across Africa. The newly established Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) seeks to bring the 55 members of the African Union together. By spring 2018, 44 states had formally joined CFTA. Predating the CFTA, regional economic communities have also been working on removing tariff and nontariff barriers to trade.

Yet, because drugs are such a highly specialized product, these efforts do not sufficiently enable the creation of regional hubs for pharmaceuticals. The African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization effort has yielded noteworthy results, with the East Africa Community countries conducting joint assessments and inspections. However, companies still cannot file a single registration recognized by neighboring countries anywhere in sub-Saharan Africa today. Until that happens, no at-scale company can realistically serve multiple countries.

Focus on drug-product formulation, but keep an eye on new technology

Focusing on the right part of the value chain will be critical to the success of a pharma sector in sub-Saharan Africa. APIs today are very scale sensitive and hard to manufacture. Most countries in the region lack the requisite chemicals sector for API production, which our modeling suggests would already be 10 to 15 percent costlier than imports from India. That makes drug-product formulation the better bet, while continuing to import APIs—for now, at least.

Looking ahead, this focus could evolve. New technologies may reduce API costs by altering scale economics to maintain competitive prices, simplifying manufacturing, or enhancing quality. Sub-Saharan Africa has the advantage of adopting cutting-edge technologies without the concern of replacing existing technologies in legacy plants. Some of the most promising technologies on the horizon include improved process chemistry, continuous manufacturing, and modular plant design. Using Ethiopia as an example, if they choose the right molecules for production, they could reduce costs by approximately 5 to 35 percent by employing improved chemical-synthesis processes, and continuous production could cut costs by another 10 to 25 percent. In addition, modular plant design could speed construction of these plants and ensure tighter quality assurance.

Upgrade the value chain

Though the focus may be on drug-product manufacturing, countries might also consider upgrading the value chain beyond just manufacturers. In sub-Saharan Africa, the distribution system is fragmented, with distributors, wholesalers, and retailers adding markups to the product. In some countries, the drug markup can almost double the manufacturer’s price by the time it reaches the end consumer. This system not only raises drug prices but also compromises quality assurance, with each step introducing the potential for improper storage, tampering, or delays, particularly as drugs near their expiration dates.

To get the value chain under control, governments might better enforce quality standards in distribution, wholesaling, and retailing, for example. Many tiny unregulated shops today don’t meet standards already on the books. If they did, it may encourage some industry consolidation and encouraging discipline that will also lead to better patient outcomes.

Some question sub-Saharan African countries’ ability to build a local pharmaceuticals industry, while others question the wisdom of doing so. The presented analyses should comfort the skeptics by demonstrating the potential for a robust local industry in certain countries under the right conditions. It is now for public- and private-sector leaders in the region to decide whether to try.